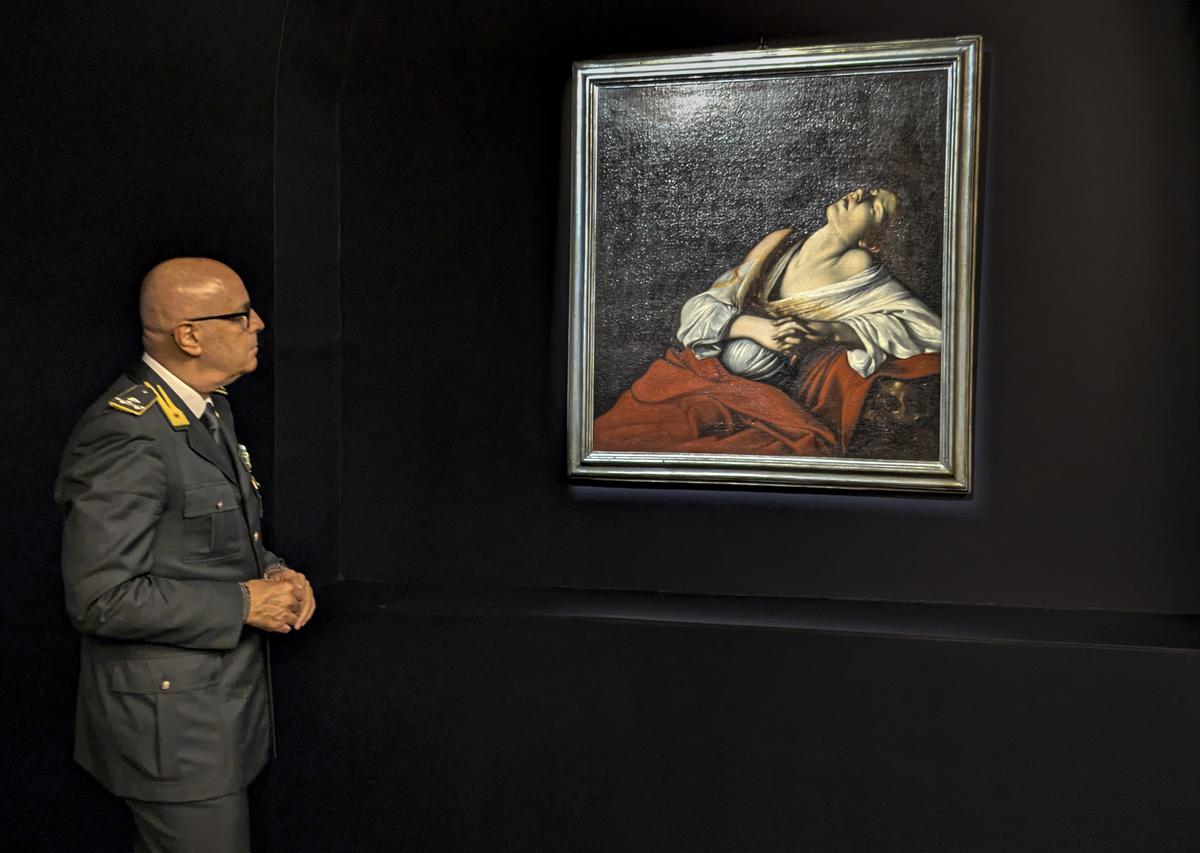

I have visited Italian painter Caravaggio in many cities — London, Florence, Rome, Venice, Paris. Now here he is, returning the visits, a guest in my hometown Bengaluru, where Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy is on display at the National Gallery of Modern Art. Caravaggio had carried the painting with him while escaping to Naples after murdering a man at a tennis court in Rome. This was in the 17th century, but the question, can you separate the art from the artist, continues to trouble us.

Caravaggio painted people from the streets (upsetting people by using a prostitute as model for the Virgin Mary). But he is said to have painted the Bengaluru work (in a manner of speaking) from memory; the memory of a love affair with a prostitute, Lena. She is imagined with her head thrown back, hair loose and shoulder exposed, fingers clasped and lips parted in ecstasy. A teardrop has begun its journey. This, in response to a resurrected Christ revealing himself. It is a picture of abandonment and loss, too. Caravaggio’s loss of his love. In combining the personal and the universal, Caravaggio pointed a way for all art.

Everything we know about Caravaggio, born Michelangelo Merisi, comes from police reports and court records of the many crimes of the artist that French writer Stendhal called “a wicked man”. Contemporaries writing a decade after his death — self-serving narratives, according to a recent biographer — give us some events. He died at 39, either murdered, or following malaria, of syphilis, or owing to lead poisoning from his paints. There are 70 or 89 or 106 paintings of his in existence — uncertainty hovered over his life, work and death.

Painting the action

Caravaggio was born in 1571, seven years after Marlowe, Shakespeare and Galileo. He was the first modern painter, creating the new world of art, literature, and science with his contemporaries.

A chalk portrait of Caravaggio (circa 1621)

He was a pioneer of modern cinematography, too. Director Martin Scorsese has acknowledged his debt to the artist who chose to paint a moment not at the beginning or at the end of an action, but “during the action… it was like modern staging in a film. It was as if we had just come in the middle of a scene and it was all happening”, as he said.

Caravaggio was his paintings. I first saw him at the National Gallery in London where his Supper at Emmaus draws you in, making you a participant in the tableau. Two disciples have walked into an inn with a man they befriended along the way. When the stranger blesses and breaks bread, they suddenly realise he is Christ. Caravaggio paints that moment of recognition. The foreshortening of the outstretched arms of one disciple and the perspective of the other about to rise abruptly make it look like a modern photograph (photography wasn’t invented for another two centuries). There is a halo over Christ cast by the light from behind the innkeeper. A basket of fruits on the edge of the table is about to tip over. A split second has been eternalised.

Over the years, I have spent hours sitting before the painting. Whenever my wife and I went to London, we joked that it was as much to see our son as to visit the painting. On our bucket list is a visit to every Caravaggio on display. It is a blessing that so many works are in churches, virtually free to view. Occasionally, you dropped a coin into a slot to light up the work as some are in dark niches.

At Rome’s Capitoline Museum, there is an unusual Caravaggio — later critics called it a ‘genre painting’ — The Fortune Tellerwhere a young man looks pleased to get his palm read by a girl. What he doesn’t notice, and we do, is the girl removing his ring as she does so.

Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy at the Italian Cultural Centre in New Delhi, before it travelled to Bengaluru

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Perfection of life or work?

Caravaggio was unique. According to a biographer, he had the advantage of not having been taught, which meant he had nothing to unlearn. He had no studio in the conventional sense. He did not draw. He never established a workshop with assistants who painted the boring stuff, he had no circle of pupils.

Yet he influenced every artist who followed. And possibly every viewer, too. It is impossible to stand outside his canvas and not feel the energy, the power and the passion within. It hits you with the force of a falling building or a charging horse.

The Caravaggio Conundrum — how do we weigh an artist’s accomplishment against his personal wickedness? — haunts us today as we contemplate the works of Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, and a host of others who provoked the cancel culture. As the poet Yeats wrote: The intellect of man is forced to choose/ perfection of the life, or of the work…

It is a choice individuals have to make for themselves.

The painting is on display at the National Gallery of Modern Art till July 6.

The writer is a prominent journalist and author.

Published – June 24, 2025 11:01 pm is